History of Male and Female Colored School No. 1

From 1878-1889, the Peale was part of the new public school system being developed in Baltimore to provide free education to African Americans in the city. Known as “Male and Female Colored School Number 1,” the building was the site of one of the first grammar schools in Baltimore’s Colored School system, and the first High School available to people of color in the State of Maryland.

Understanding the historic context from which Baltimore’s schools have been formed has never had greater urgency and importance for the Baltimore community. Up until now, the story of the ‘colored’ school system and education in Baltimore has never been comprehensively researched and presented in a way that invites public engagement.

We are grateful for the following people for their work on this project:

- Tonika D. Berkley, MAA, Research Coordinator and Curator, Male and Female Colored Grammar and High School 1 at the Peale Center Research Project

- Dr. Iris L. Barnes, Curator, Lillie Carroll Jackson Civil Rights Museum, Executive Director of Hosanna School Museum in Darlington, Maryland

- Dr. Mary Ellen Hayward, Architectural Historian, Preservation Consultant and Museum Consultant, Member, Board of Directors of the Peale Center for Baltimore History and Architecture

- Lisa Rose Lamson, Lord Baltimore Research Fellow, Maryland Historical Society, PhD Candidate in American History at Marquette University, Milwaukee, Wisconsin

- Dean Krimmel, Interpretive Planner and Exhibit Developer, Member, Board of Directors of the Peale Center for Baltimore History and Architecture

- Dr. Brian Morrison, Founder & President, The William J. Watkins Sr. Educational Institute, Inc.

This project has been supported by the Maryland Heritage Areas Authority (MHAA).

Early History (1864-1867)

1864-1867

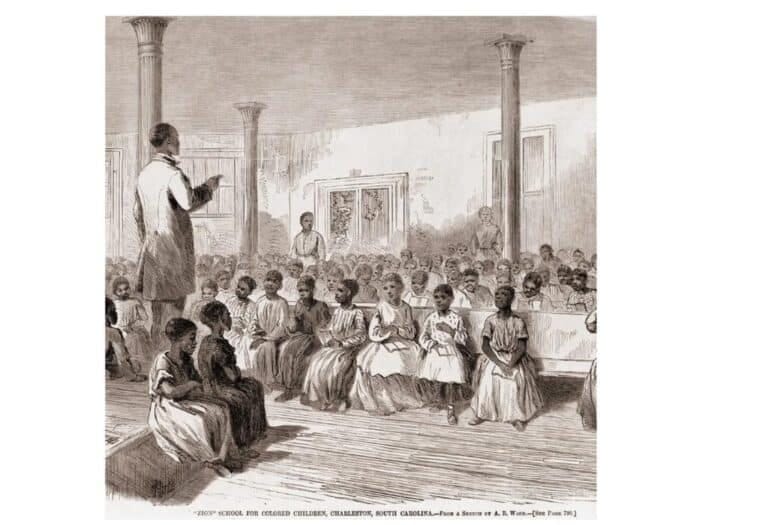

The early history of Colored School No.1 (Male and Female) begins with the Baltimore Association for the Moral and Intellectual Improvement of the Negro. What would become Colored School No. 1 was the largest school operated by the Association from 1864 to 1867, the period that they were responsible for the operation of the schools for colored children in Baltimore. When they turned over the schools under their control to the Board of School Commissioners in 1867, that school disbanded. It was centrally located in a building on Calvert and Saratoga streets.

The Baltimore Association oversaw operations of the colored schools in Baltimore for two school years, from 1864-1866. In their third year of operation they transferred the schools they supervised to the city’s Board of School Commissioners. When the city took responsibility of the colored schools, Colored School No. 1 (Male and Female) were housed in the Douglass Institute located on Lexington Street. Douglass Institute was an independent African American institution that was used for civic and political events in the African American community. In the first year of the city’s operation of the colored schools Colored School No.1 (male and female) had the largest number of students, 200 according to the 39th Report of the Board of School Commissioners.

Fighting for Expanded Education

1869-1889

All of the early schools established for African American students were primary schools. There were no grammar or high schools. In 1869 the Board of School Commissioners approved a resolution to allow the primary schools to add grammar grades to the primary schools. In the first year the colored schools were in operation, the superintendent had requested the school board to open two grammar schools. One of the major initiatives of the African American community was to expand the curriculum for the high school level, a fight that would take 16 years to win. However, by 1877 Baltimore’s African American community had gained a grammar school, located at 61 Saratoga Street.

Colored Schools No. 1, Male and Female remained at the Douglass Institute from 1867 until 1879 when the male and female divisions were split. Female Colored School No. 1 was moved to 61 Saratoga Street, the location of Colored Grammar School No. 1. Male Colored School No. 1 and Colored Grammar School No. 1 were moved to the “Old City Hall,” the Peale building, on Holliday Street. In 1882 the African American community’s demands for a high school were met when the city council authorized the establishment of a colored high school. In 1883, the Board of School Commissioners followed the same model they used in establishing grammar schools.

The Evolving School

Instead of opening a new, separate high school, they simply added two grades to Grammar Colored School No. 1, located in the Peale Building. While the African American community now had a high school, the school had a limited curriculum. Only two grades were added to the grammar school and it did not confer “testimonials” on those who completed the curriculum. In order to receive testimonials students had to complete 4 years of high school. Testimonials were significant because they authorized recipients to teach in the primary and grammar schools.

The High and Grammar Colored School remained at the Holiday Street location until they were moved to Saratoga Street in 1889. Male Colored School No. 1 remained at the Holiday Street location until 1891 when it was moved to the Saratoga Street location as well. Throughout the later part of the 19th century African American Baltimoreans sought to gain full access to the educational opportunities the city offered to its white citizens. They often found their children with inadequate books, supplies, materials and facilities. When the city council authorized funds for the construction of a colored high school it was a major victory in their quest to achieve their educational goals. The facilities in the “old city hall” were inadequate, at best, for the proper instruction of the students there. Complaints of the teachers and the need for additional space by the water department further led to the eventual departure of Male Colored School No. 1 in 1891 ending the use of the Peale building as a colored school.

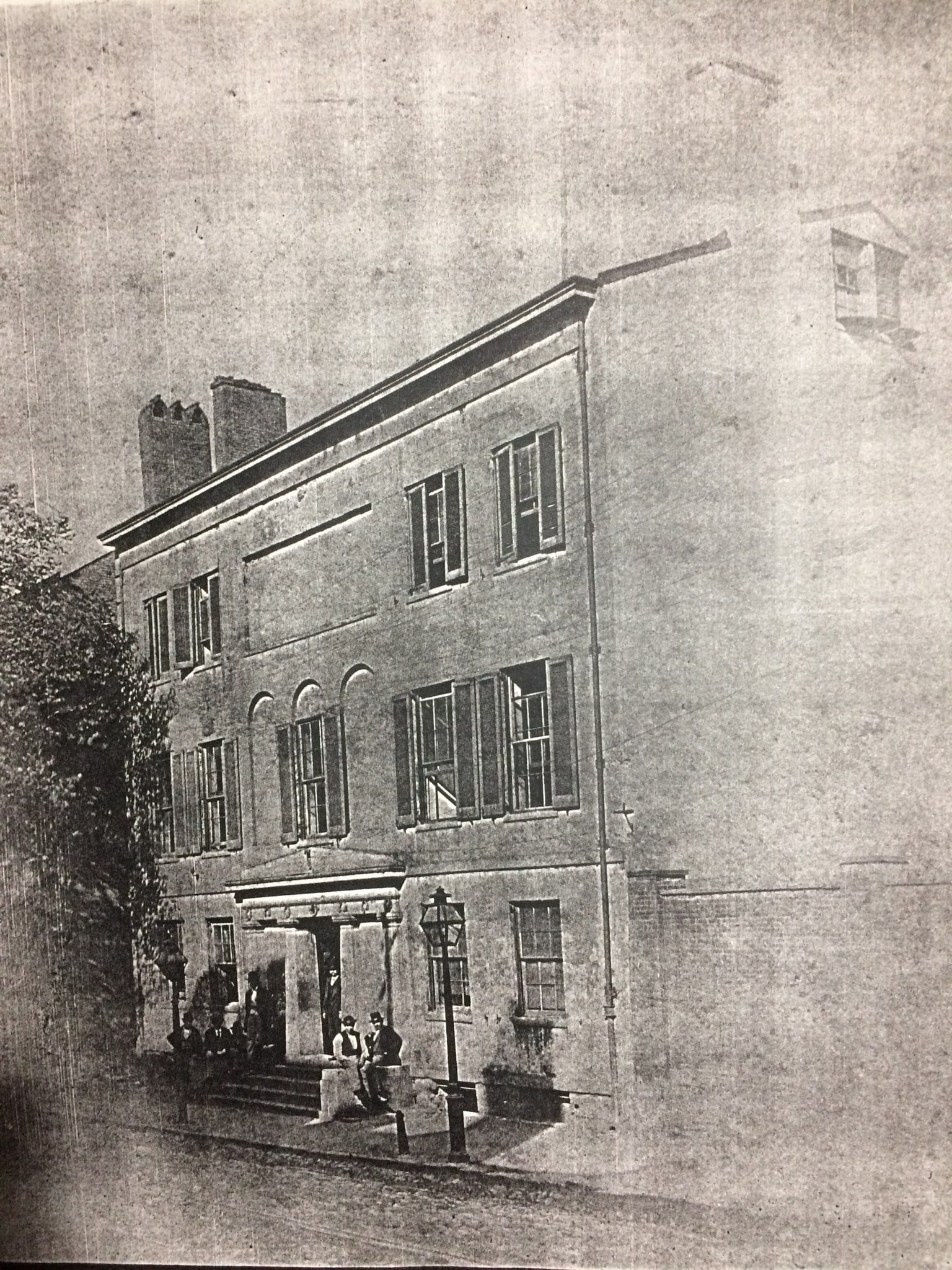

The Peale Building in 1877

A year after this photo was taken, the Peale became a school. The block where the building was located was an industrial area in the 1870s. To the north were also industrial districts made of machine shops, gasworks, iron foundries, carriage factories, stables, and warehouses. The area became overrun with industrial waste and human filth.

The Peale building as seen in an 1877 photo. BCLM Collection MC 10410, Maryland Historical Society

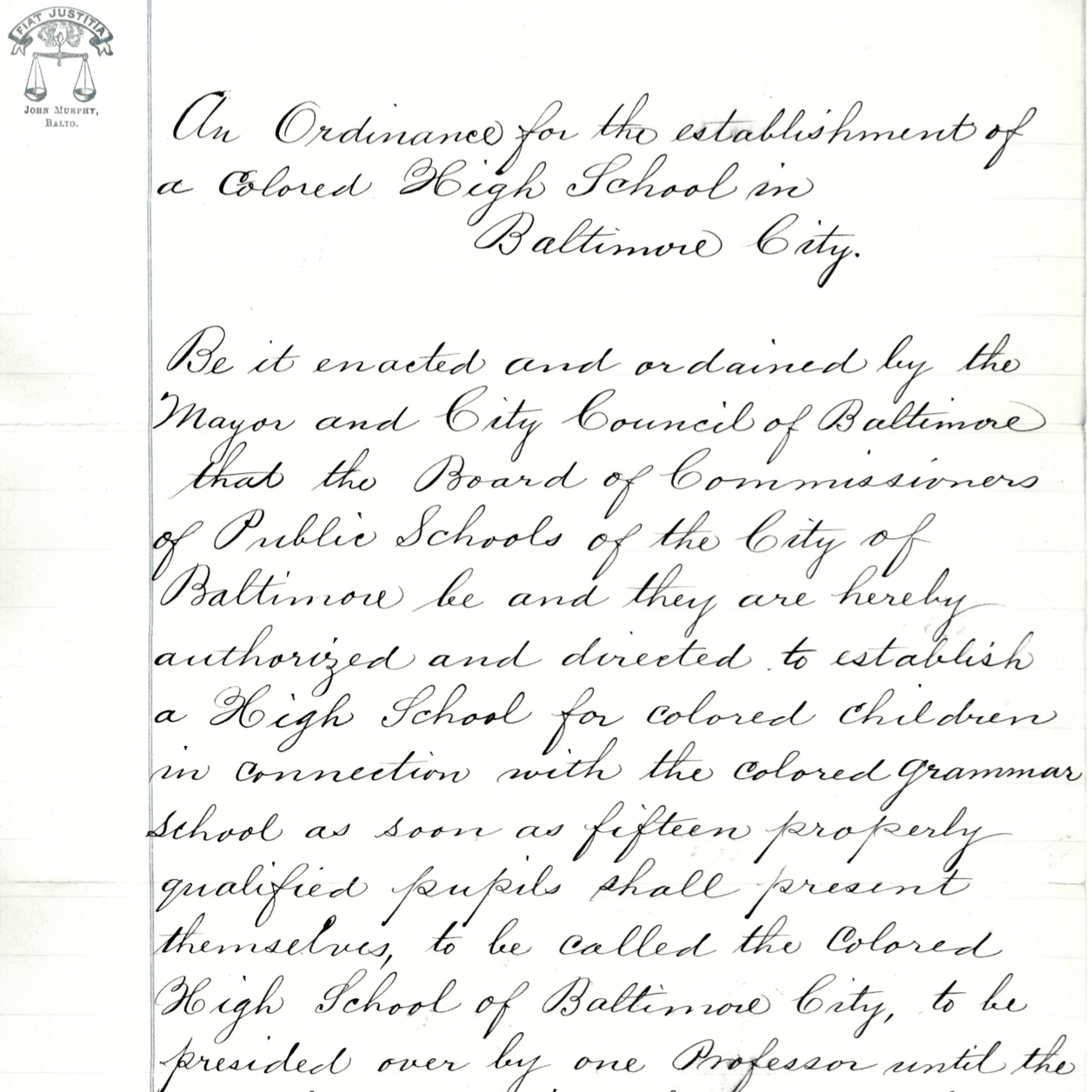

1882 Ordinance Established

On November 1, 1882, the City of Baltimore adopted an ordinance for the establishment of Male and Female Colored High School No. 1, to be house at the Peale building. It is “…expedient to organize a high school class in conjunction with the colored grammar school No. 1 as soon as there are 15 pupils sufficiently advanced for promotion.”

Ordinance courtesy of the Baltimore City Archives; Quote from APRIL 5, 1882, Baltimore Sun

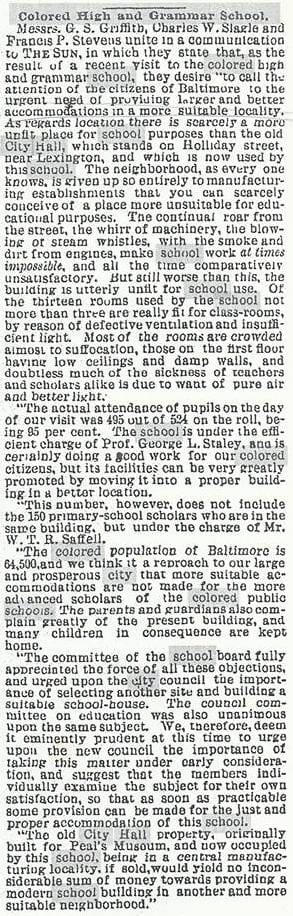

Newspaper Article, 1885

The Baltimore Sun wrote an evaluation of Male and Female Colored High and Grammar School No.1, based on a review from a team of school board members and the principal. They commented on the school being in an industrial area, the hazardous conditions inside the building, and overcrowding. It “…is not a suitable one in scarcely any respect.”

February 18, 1885, Baltimore Sun

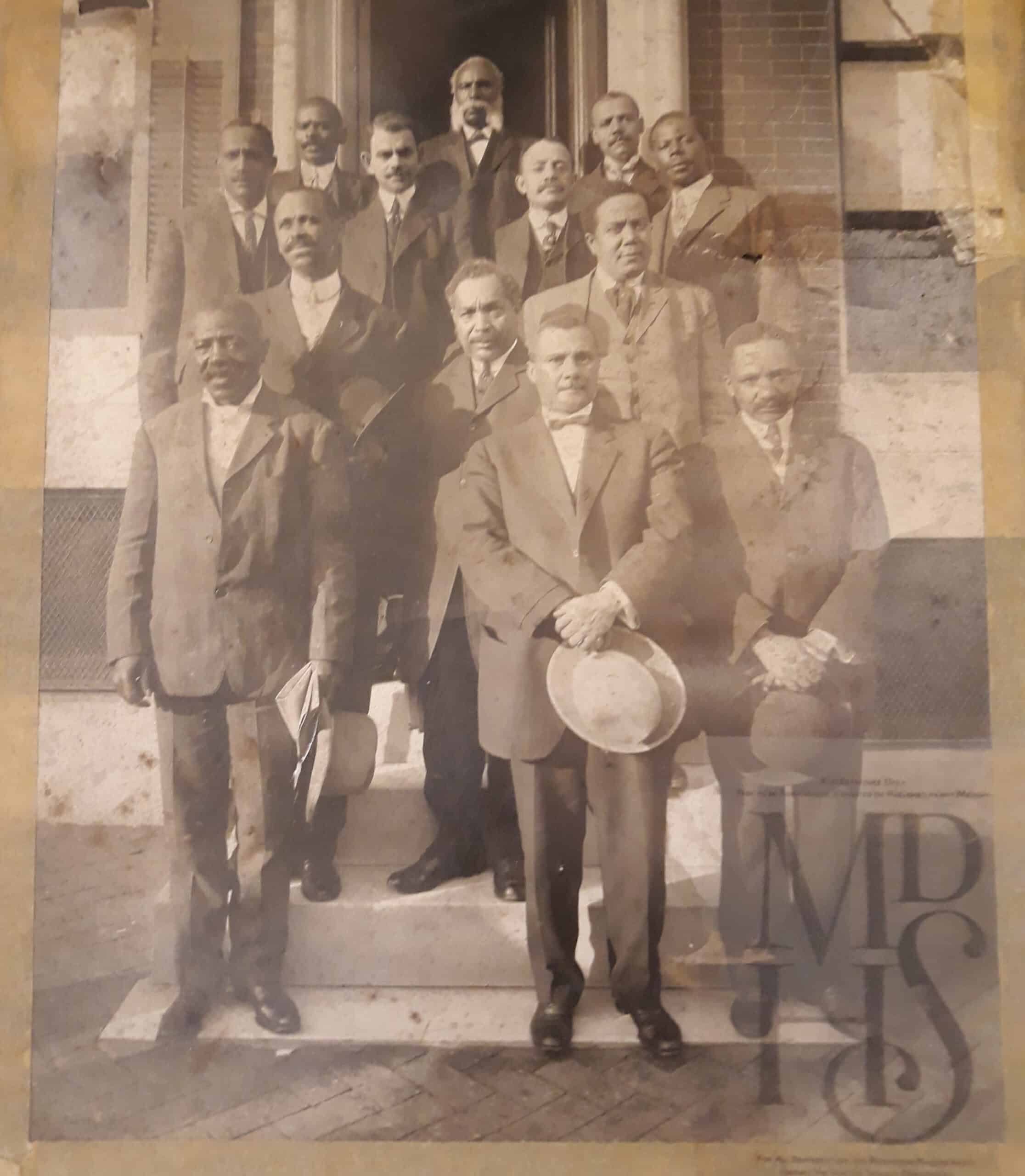

Brotherhood of Liberty, ca. 1900

The Mutual United Brotherhood of Liberty championed equitable education for Black students. It was founded by Rev. Harvey Johnson and several clergymen and was the first Civil Rights organization in Baltimore and one of the first in the nation. In the late 1890s, The Mutual United Brotherhood of Liberty undertook numerous protests against educational inequality.

Photo taken in front of the home of Reverend Johnson (center, top row); attorneys H.S. Cummings, G. Pendleton, Ashby Hawkins, and C.C. Fitzgerald Harry Scythe Cummings. Photo Collection, Courtesy of Maryland Center for History and Culture

The Legacy of the Peale Building

What can be said about the Peale building’s role in the education of Baltimore’s African American community? For one, it is a symbol of progress towards the African American community’s struggle to gain full access to the city’s public schools. Serving as the location for the first colored high school in the city, a major victory and milestone for Baltimore’s African American community. As such, it represents a significant step towards gaining access to the benefits of full citizenship – education. The city’s earliest African American educators elected to teaching positions in the city’s colored schools attended school there. Within a year of opening the new colored high school, the city council passed an ordinance authorizing the Board of School Commissioners to allow graduates to teach in the colored schools.

This too, was a major milestone and victory for Baltimore’s African American community. One of the major goals of the African American community was a campaign of “colored teachers for the colored schools.” The granting of testimonials to graduates of the Colored High School that attended when it was located in the Peale building is another way in which the location was significant. The Peale’s role cannot be viewed in isolation. It was part of the larger story of African American Baltimorean’s ongoing quest to gain full access to the city’s public schools and citizenship rights.

Submitted by Dr. Brian C. Morrison

This Project has been financed in part with State Funds from the Maryland Heritage Areas Authority, an instrumentality of the State of Maryland. However, the contents and opinions do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Maryland Heritage Areas Authority.